Knut Lundmark eng

This material is still in progress... Please return at a later time.

The school house, Krokträsk, ca 1899.

The school house, Krokträsk, ca 1899.

When Martin Johnson, who passed away in 2011, Knut Lundmark's close friend and co-worker, compiled the book Knut Lundmark och Världsrymdens erövring (’Knut Lundmark and Man´s March into Spacè´)the Conquest of the World Space’) - published by Värld och Vetandes Förlag, 1961- a row of astronomers and other scientists participated in the memorandum (Niels Bohr, Werner von Braun, Milton L Humason, Carl Schalén, Harlow Shapley, Fritz Zwicky, B. A. Vorontsov-Velyaminov, Per Collinder et al.)

Martin Johnson, who also had his roots in the North of Sweden, told in his own words about Lundmark's barren childhood and growing up years.

This was his contribution (in Swedish): Martin Johnson: Lundmarks uppväxt

Knut Lundmark at his PhD graduationIn 1920 presented his 78 page doctoral dissertation (including one plate with the Magellanic Clouds) entitled ‘’. Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences's documents. 60:8 Stockholm.

Knut Lundmark at his PhD graduationIn 1920 presented his 78 page doctoral dissertation (including one plate with the Magellanic Clouds) entitled ‘’. Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences's documents. 60:8 Stockholm.

Together with the legend Heber D Curtis at the Lick Observatory, Mount Hamilton, California, Lundmark was at that time one of the few representatives of the galaxy theory, that is, the spiral nebulae were, in fact, remote Milky Ways. ‘...By this time, Curtis and Lundmark must be the only defenders of the island-universe theory ...’ Adrian van Maanen wrote in a letter to Harlow Shapley in 1921. That was a correct summary.

The prominent part of the discussion were how distances could be determined. By comparing the novas light intensities below the maximum in M31 with those in our own galaxy, Lundmark could place M31 at least 650,000 light years away (about a quarter of today's modern measurements). The starting point was his determination of their absolute maximum magnitude to about -7.

Lundmark saw it as a statistical impossibility that the 11 novas observed in M31 did not belong to the system; No novas had been seen in the area around M31 on the sky. Thus they must belong to the celestial body.

Other ‘distance indicators’ were also used - for example, Wolf's photographies of dark dust clouds in spiral galaxies, whose width was compared to the width of the clouds in the Milky Way.

Even his studies of the apparent sizes of spirals were included in the determination of their respective distances. The starting point was that the spirals were of equal size.

The dissertation is dated Upsala Observatory May 15, 1919, and sums in bold the parallax of the Andromeda Spiral to:

0",0000051+/-0",0000018 (p.e.)

with a weighted average of 0",0000060.

In an appendix, Lundmark adds that since the main work was completed, a total of 15 novae have been observed in M31, but the newly added did not change his conclusions, at any crucial point .

In the dissertation, Lundmark is stumbling close to introducing the concept of ‘supernova’, but is content to describe Hartwigs nova 1885 (= S And) as belonging to ‘a giant type’, while the other 14 are described as ‘dwarfs’. Novae in spirals other than M31 probably belonged to this circuit of ‘the brightest kinds’.

A side result of Lundmark's analysis was that the dimensions of the Milky Way had to be reduced to perhaps below 100,000 light years in diameter.

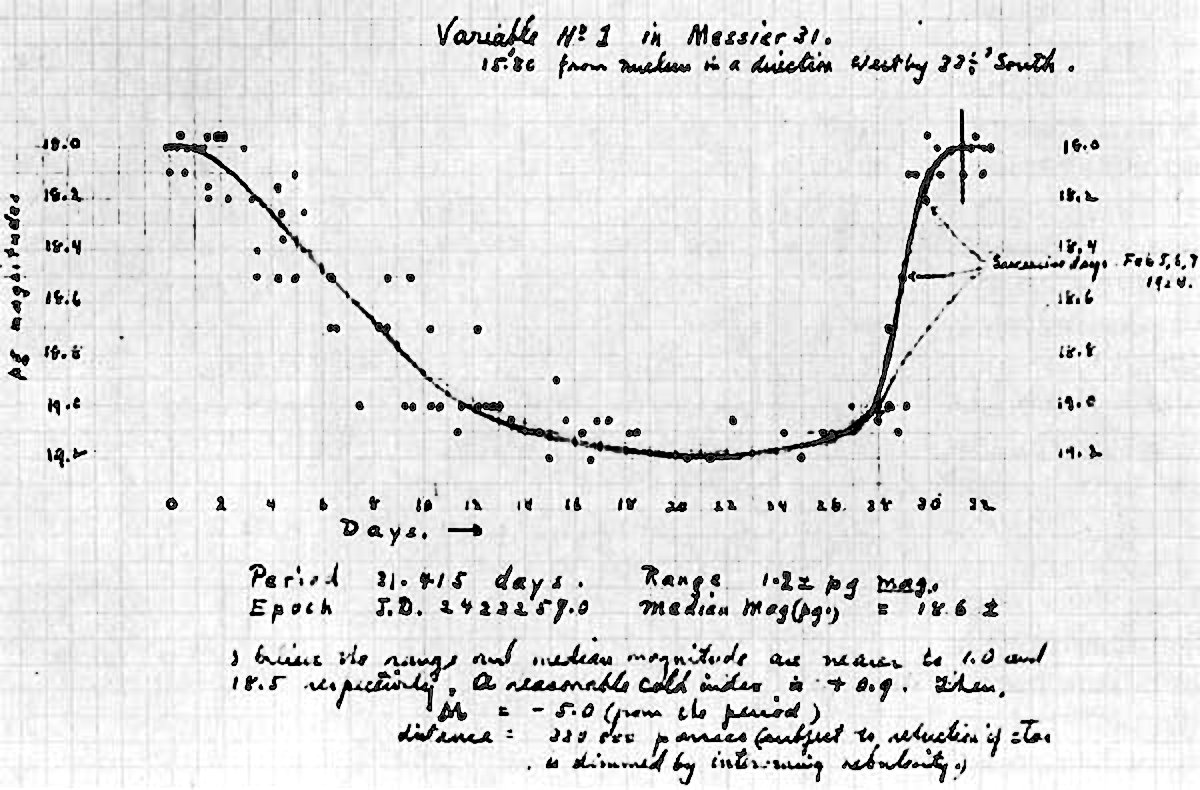

The discussion was not closed until Edwin Hubble secured a cepheid variable in M31 1924 - the letter of the discovery and a light curve (see above) was received by Harlow Shapley, who said that the Milky Way was a giant star system with spiral nebulae like nearby ‘raisins in the Milky Way’ to throw in the towel and point out:

The discussion was not closed until Edwin Hubble secured a cepheid variable in M31 1924 - the letter of the discovery and a light curve (see above) was received by Harlow Shapley, who said that the Milky Way was a giant star system with spiral nebulae like nearby ‘raisins in the Milky Way’ to throw in the towel and point out:

– Here is the letter that has destroyed my universe.

A good proof of Lundmark and Curtis friendship and collegiality is the letter Curtis wrote in 1938 to Lundmark - see the ‘Letters’ tab on this website.

Lundmark's dissertation is, no more no less, modern astronomical history, the dissertation contributing to a classic paradigm shift of almost Copernic style. It was also cited by Curtis in ‘The Great Debate’, the famous debate of the existence or non-existence of the ‘island universe theory’, between Curtis and Harlow Shapley.

One of Lundmark's specialties continued to be metagalactic distance indicators, how the use of novas, supernovas, super giants, cepheids, globular clusters etc could be used to determine distance to galaxies and galaxy clusters. How far the astronomy's state of the art has reached, he summed up in late 1956 in Vistas in Astonomy, Vol. 2, the article ‘On Metagalactic Distance-Indicators’.

The history of Lundmark's life can be read in his memoir, a chapter in ’Astronomiska upptäckter, del II’ (’Astronomical Discoveries, Part II’) (1952), and in the memorial ’Knut Lundmark och världsrymdens erövring, en minnesskrift' (' Knut Lundmark and man´s march into space, a memorial volume’) (1961).

Important information about Knut Lundmark's life and work is found in Johan Kärnfelt's (historian of ideas and science) both writings ’Till stjärnorna - Studier i populärastronomins vetenskapshistoria under tidigt svenskt 1900-tal’ (’To the stars - Studies on the history of popular astronomy in early Swedish 1900s’) (2004) and ’Allt mellan himmel och jord - Om Knut Lundmark, astronomin och den publika kunskapsbildningen’ (’Everything under the sun : Knut Lundmark, astronomy and the public appropriation of science ’) (2009).

Naturally, in some writings that are focusing on Lund's observatory, the history of Knut Lundmark is told: ’Astronomien i Lund 1667-1936’ (’Astronomy in Lund 1667-1936’) (written by Lundmark himself, published 1937), ’ Astronomiska observatoriet vid Lunds universitet’ (’Astronomical Observatory at Lund University’) by Carl Schalén, Nils Hansson and Arvid Leide (1968) and ’Lundaögon mot stjärnorna - Astronomin i Lund under fem sekler’ (’The sky as seen from Lund - Astronomy in Lund for five centuries’) (2003, eds. Lennart Lindegren and Ingemar Lundström).

Lundmark's pioneering effort in the galaxy astronomy is discussed in Gustav Holmberg's dissertation in 1999, entitled ’Reaching for the Stars: Studies in the History of Swedish Stellar and Nebular Astronomy, 1860-1940’.

Anita Sundman also wrote about Knut Lundmark in Nationalencyklopedin (the Swedish National Encyclopedia) and gave us a rich, full-bodied personal history in Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon( the Swedish Biographical Dictionary). From the latter (published by the Swedish National Archives (Riksarkivet)), the entire Lundmark depiction is shown below in Swedish.

Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon: Lundmark

C V Charlier, Lundmark's predecessor.

C V Charlier, Lundmark's predecessor.

A very important source of knowledge to the cause of the professorial battle in Lund, when the successor to C V Charlier in 1928 was to be appointed, is the book by Johan Kärnfelt (’To The Stars - Studies in the Popular Astronomy's History of Science in Early Swedish 1900s’, 2004). It's an exciting story about new (i.e. galaxy research) and old (i.e. stellar statistics) astronomy, about strong personalities, about conscious misunderstandings, about intrigues and secret meetings, about popular science's status in the research community, etc.

It is doubtful if we can claim that Lundmark, who eventually was appointed professor, used shiny weapons in the heat of the dispute and the appeal.

With Johan Kärnfelt's permission we here reproduce pages 260-279 from his very interesting book (Swedish only).

Kärnfelt: s 260-279