The Popularizer

Knut Lundmark was an engaged advocate for his science and its history. This could be noticed on all levels: He wrote popular science in the mass media of its time, newspapers, magazines, he published popular science books, traveled around the country making speeches on astronomy for the public – and furthermore he was busy in the new media, radio.

Gunnar Ollén, legendary director for Swedish Radio in Malmö, later also TV-director, told in a memory book 1961 about how Lundmark was as a radioman (right).

In a unique talk show Lundmark and the Nobel prize winner in literature 1974 Harry Martinson (the forthcoming creator of Aniara (link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aniara) debate current astronomy under a headline called “A tab of the Universe”. Martinson asks, not so little pessimistic and abject in relation to mans place in a desolate and vacuous universe, Lundmark replies and straightens out. Martinson is insecure on behalf of man in this eternal cosmos. Lundmark feels at least partly at home, but is distrustful about the newest cosmology, which in time and space limits “his” universe.

This talk between two seekers is in ameritorious way analysed in Anita Sundman’s biography of Lundmark The Liberated Heaven: A portrait of Knut Lundmark (Den befriade himlen: Ett porträtt av Knut Lundmark) pages 119-127.

On Swedish Radio’s SR Minnen this unique recording is preserved (Swedish): Lyssna: En flik av universum

In Lundmark's bequeathed papers you can find among other things this hand-written manuscript for a radio seminar , which has never been published.

FLIPBOOK KOMMER HÄR

Knut Lundmark published a lot of popular science books. It started in 1922 with Spiralnebulosorna: ett nutida astronomiskt forskningsproblem* ["Spiral nebulae: a contemporary astronomical research problem"] (Studentföreningen Verdandis småskrifter), after that followed publications with titles like

Knut Lundmark published a lot of popular science books. It started in 1922 with Spiralnebulosorna: ett nutida astronomiskt forskningsproblem* ["Spiral nebulae: a contemporary astronomical research problem"] (Studentföreningen Verdandis småskrifter), after that followed publications with titles like

Från kaos till kosmos: några utdrag ur den astronomiska världsbildens utvecklingshistoria (1934) ["From chaos to cosmos: some excerpts from the development history of the astronomical conception"]

Livets välde: till frågan om världarnas beboelighet. Part 1 (1935; ["Life’s dominion: To the question of habitability of the worlds"] the second part was never published)

Det växande världsalltet (1941), ["The growing cosmos"]

Solförmörkelser förr och nu (1945), ["Solar Eclipses in the past and now"]

Astronomiska upptäckter: några glimtar från en flertusenårig vetenskaplig utveckling (two parts, 1950, 1951), ["Astronomical discoveries: some glimpses from a scientific development during millenia"]

Världar utan gräns (1951), ["Worlds without limits"]

Dagmörkret över Sydsverige den 30 juni 1954 (1953). ["Day of darkness over Southern Sweden 30th of June 1954"]

Ut i världsrymden(1956) ["Out in space"].

His magnum opus was printed during World War II with its paper rationing etc – Nya Himlar (1943) ["New Heavens"], published by Nordisk Rotogravyr and dedicated to his wife Birgitta.

His magnum opus was printed during World War II with its paper rationing etc – Nya Himlar (1943) ["New Heavens"], published by Nordisk Rotogravyr and dedicated to his wife Birgitta.

This mighty work in a numbered folio edition (500) – including lots of beautiful illustrations, several in colours – describes on almost 800 pages the historical evolution of astronomy up until the fight about the nature of the galaxies, where Lundmark of course touches on his own pioneering role.

Among owners of this book were the King of Sweden as well as the then prime minister Per Albin Hansson and other celebrities.

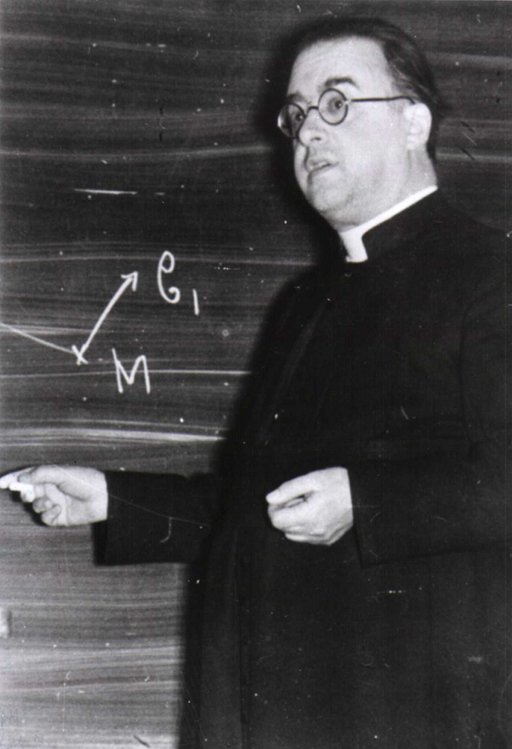

As an example of Lundmarks own style and tone, we here publish some lines with among other things the memory of a meeting with George Lemaître – Lundmark could already then, in 1943, confirm what later astronomy historians have affirmed, that Lemaitre was onto the expansion of the universe before Edwin Hubble.

"Meanwhile, this escape of the island universes from the observer had been predicted as a relativistic phenomenon by Louvain professor G Lemaître.

The story of his discovery is extremely remarkable and shows, unfortunately, that it certainly is not always so certain that a work is immediately recognised by its inherent power and its inalienable value.

At the I.A.U General Assembly in Leiden in 1928, the author met a young, sympathetic abbot, called Lemaître, who was very interested in the issue of nebulae motion. He had shown that Einstein's field equations allowed a simple solution different to the two that Einstein himself and de Sitter had presented. According to Lemaître's solution, the universe expanded linearly and thus the distant galaxies must exhibit very large red shifts in the spectra.

Since the author was not sufficiently acquainted with the theory of relativity to be able to assess the value of his effort, Lemaître was referred to Eddington and de Sitter. Admittedly, the bibliographically very fine original investigation had been sent to them, but for some reason it was not noticed. Only a few years later, when Eddington entered this area and Lemaître pointed out his effort, Eddington reprinted L's thesis and emphasized the importance of it.

When we met at the next I.A.U. in Cambridge, Lemaître did not have to adhere to astronomers by the author's magnitude, because then he was one of the leading names. Rarely have we seen a well-deserved world fame reached so quickly.”

Lundmark participated as co-author in a number of extra-scientific books. Perhaps most surprising is his contribution, the very last, to the book Vad Kristus lärt mig (What Christ taught me) (Nature and Culture, 1957). Lundmark's religious beliefs originated from a poor home, which was strongly Lutheran, spanned to the scientist's agnosticism and, finally, to the older scientist's insights into the deep mystique of the existence. He would have liked the new theories of multiverse.